Videos of forming embryonic blood vessels reveal the presence of unusual cells and the unexpected role of a well-known gene in creating blood

One of the first organ systems to form and function in the embryo is the cardiovascular system: The embryo urgently needs blood vessels for distributing oxygen and nutrients so it can grow and develop. In fact, this developmental process starts so early, scientists still have many unresolved questions on the origin of the primitive heart and blood vessels. How do the first cells that are destined to become part of this system – the progenitors – participate in shaping the developed cardiovascular system?

Dr. Lyad Zamir, a former PhD student in the lab of Prof. Eldad Tzahor in the Molecular Cell Biology Department of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, developed a method to image the earliest cardiovascular progenitors and track them and their descendants through the developing embryo in real time. His movies took place in fertilized chicken eggs, in which a complex network of blood vessels forms within the yolk sac to nourish the embryo. The findings of this research were recently published in eLife.

Working in collaboration with the lab of Prof. Richard Harvey of the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute and University of New South Wales, Australia, Tzahor and Zamir focused on a gene called Nkx2-5. This gene encodes a transcription factor – a regulatory protein that controls the expression of whole batteries of other genes – in this case, those involved in the development of the heart. “When you knock out Nkx2-5 in mouse embryos, you see severe defects in the vasculature, as well as the heart. But the gene had only just recently been tied to the development of blood vessels,” says Tzahor. “The new study revealed that Nkx2-5, in addition to directing the development of the heart, plays a central role in the genesis of the very first blood vessels and indeed the formation of blood. This occurs independently of its roles in the heart.”

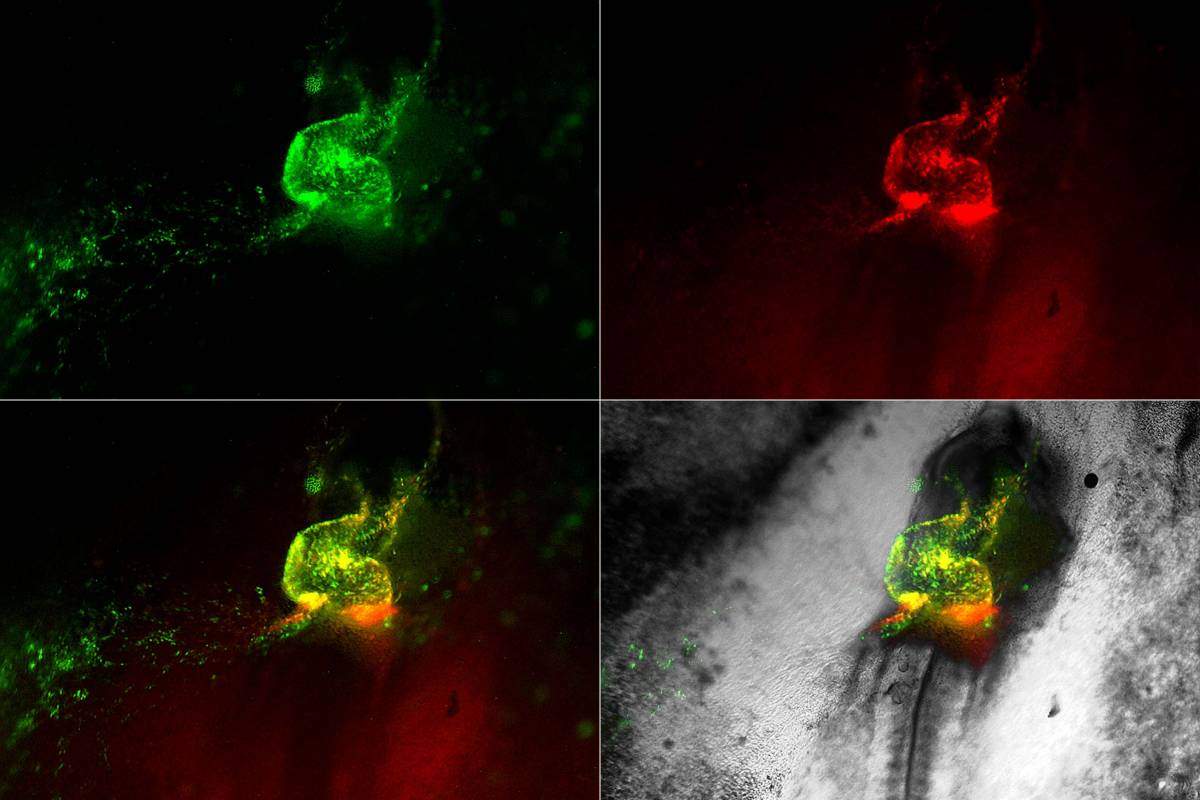

Heart development in motion. Early cardiovascular cells (in green and red) migrate towards the midline of a living chick embryo where they fuse to form the embryonic heart tube

Looking at the onset of Nkx2-5 expression in chick embryos and later in mice embryos, the team revealed the existence of progenitor cells called hemangioblasts. These cells give rise to both the blood and vascular progenitor cells – those that lead to the formation of blood vessels. These unique cells are created from the mesoderm – the middle layer of cells that appears in the developing embryo when it takes its first major step toward complexity in a process called gastrulation. Researchers have been hotly debating the existence of hemangioblasts and, if they do exist, their possible function.

Returning to the films in the chick embryos, the researchers could see the hemangioblasts moving to create “blood islands,” which form within the primitive embryonic vessels. The researchers were surprised to observe that some of the hemangioblast cells were also moving into the heart, where they formed blood stem cells. This helped make sense of other studies revealing that the early heart tube contains cells that appear to assist, along with other sites in the embryo, in generating blood cells. The researchers also identified specialized Nkx2-5 expressing cells within the lining of the newly formed aorta – one of the major blood vessels in the embryo – where they appeared to “bud off” to produce new blood cells. Later on in development, these specialized cells move into the liver, where they give rise to the blood-forming stem cells that are found in the fetus.

To check the results obtained in chick embryos, the researchers applied genetic cell labeling techniques in mouse embryos. They showed that a population of Nkx2-5-expressing hemangioblasts arises in the yolk sac at around that same time the cells in the embryo proper begin to express Nkx2-5 and form the heart. This finding provides evidence that the origin of cells that form the circulatory system has been conserved throughout evolution.

Tzahor: “Even 20 years after one of the ‘master genes’ for heart development was discovered, we have managed to write a new story about its action, showing that it works briefly at a very early stage in development in the formation of vessels and blood – before the main action takes place in the heart. We have provided solid evidence for the existence of these very early cells and their contribution to heart and vascular development.”

Because these findings reveal the early origins of at least some of the blood-forming stem cells in the embryo, they may be especially helpful in research into diseases affecting the cardiovascular system.

Prof. Eldad Tzahor’s research is supported by the Yad Abraham Research Center for Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy, which he heads; the Henry Krenter Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Genomics; the Daniel S. Shapiro Cardiovascular Research Fund; and the European Research Council.

Recent Comments