Reducing the need for immune suppression could extend to other biomedical advances

Mismatched bone marrow transplants now save the lives of thousands of patients with leukemia and other blood malignancies, but these transplants can be risky. The patients’ immune systems need to be strongly suppressed in preparation for the transplant, leaving them vulnerable to infection immediately afterwards. In a new study reported recently in Blood Advances, Prof. Yair Reisner and his team at the Weizmann Institute of Science, together with Prof. Franco Aversa and other physicians at the University of Parma, developed a method for dramatically reducing the need for immune suppression before and after the mismatched transplant. This method may lead not only to safer bone marrow transplants – it could also facilitate organ transplantation and help enhance cellular therapies.

The new approach builds on the prior work of Reisner, who more than two decades ago developed a strategy for making mismatched bone marrow transplants possibleby using extremely large numbers of stem cells from the donor’s bone marrow. The sheer volume of the “megadose” transplant helps to overwhelm the recipient’s rejection mechanisms. The reverse problem – the donor marrow attacking the recipient, or graft-versus-host disease – is averted by stripping the marrow in advance of the major “attackers,” the immune T cells.

To reduce the need for suppressing the immune system before or after a mismatched transplant, Reisner and the Italian physicians combined the megadose method with another strategy that has until now been practiced by physicians in a different context. The strategy consists of treating patients with an anti-cancer drug – cyclophosphamide, abbreviated as PTCY – shortly after the transplant. “PTCY kills dividing cells, and the cells that are rapidly dividing after the transplant are the recipient’s T cells, which raise their heads because they’ve identified the donor marrow and are trying to reject it,” Reisner said. “Since PTCY doesn’t kill cells that don’t divide, it doesn’t harm the rest of the patient’s immune system.”

Toleration both under and on the skin

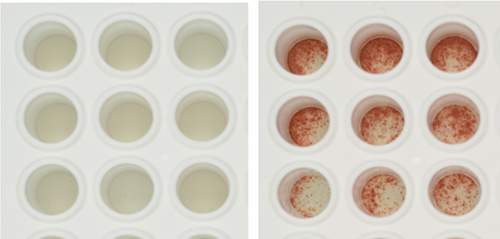

In studies in mice, Reisner showed that a megadose stem cell transplant followed by the use of PTCY resulted in a state known as immune tolerance, which is viewed as a holy grail of transplantation: The recipient’s immune system declines to reject donor cells and tissues. Mice treated with the combined approach had become so “tolerant” to the donor that after bone marrow transplantation, they did not reject skin grafts from the same donor, despite receiving no immunosuppressive drugs.

Following the success of the mouse studies, Prof. Franco Aversa and his team used the combined method in three cancer patients – two with multiple myeloma and one with Hodgkin’s lymphoma – all treated with mismatched bone marrow transplants. In two patients, the transplanted marrow engrafted promptly, even though they had been prepared for the transplantation by very low radiation: in one case 80% lower and in another case 70% lower than the usual dose. In the third patient, the engraftment was successful only following preparation with regular, high-dose radiation. The disease went into remission in all three patients, and upon further testing, the two treated with very low radiation revealed immune tolerance toward donor cells.

If the development of this form of immune tolerance is confirmed in larger studies, it could potentially enable the subsequent transplantation of such organs as a kidney or part of the liver from the same person, usually a family member, who had donated the bone marrow – without any need for the post-transplant suppression of the immune system. The method could also help in administering cell therapy to cancer patients in need of subsequent infusions of immune cells from the original bone marrow donor.

Furthermore, the safer approach could help extend the use of mismatched bone marrow transplants to elderly patients who cannot tolerate the current harsh immune suppression. The approach could also render mismatched transplants an attractive option for patients with such blood disorders as sickle cell anemia, thalassemia and a variety of autoimmune diseases, for which the use of the risky transplants is not presently justified because their diseases are not immediately life threatening.

Mice treated with the combined approach had become so “tolerant” to the donor that after bone marrow transplantation, they did not reject skin grafts from the same donor

Dr. Esther Bachar-Lustig in Prof. Reisner’s team made a major contribution to this study. The team also included Drs. Noga Or-Geva and Yael Zlotnikov-Klionsky. The Italian team, apart from Prof. Aversa, included Prof. Massimo Martelli of the University of Perugia; Drs. Lucia Prezioso, Sabrina Bonomini, Ilenia Manfra, Alessandro Monti, Chiara Schifano, Gabriella Sammarelli, Maria Sassi, Maurizio Soli, Silvia Giuliodori, Magda Benecchi and Nicola Giuliani of the University of Parma; and Drs. Frank Lohr and Silvia Pratissoli of the University of Modena.

Prof. Yair Reisner’s research is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; and Roberto and Renata Ruhman, Brazil. Prof. Reisner is the incumbent of the Henry H. Drake Professorial Chair of Immunology.

Recent Comments